Last Thursday marked the announcement of a set of landmark agreements among leading apparel brands, a coalition of labor unions and women’s rights advocates, and a major apparel supplier to combat gender-based violence and harassment in Lesotho’s garment sector. These enforceable agreements—with Levi Strauss & Co., The Children’s Place, and Kontoor Brands—link the each of the brands’ ongoing business with the supplier, Nien Hsing Textile Co., to the supplier’s acceptance of and cooperation with a worker-led program to eliminate sexual harassment and abuse. The program features an independent complaint investigation body with the power to direct punishment of abusive managers and supervisors, up to and including dismissal.

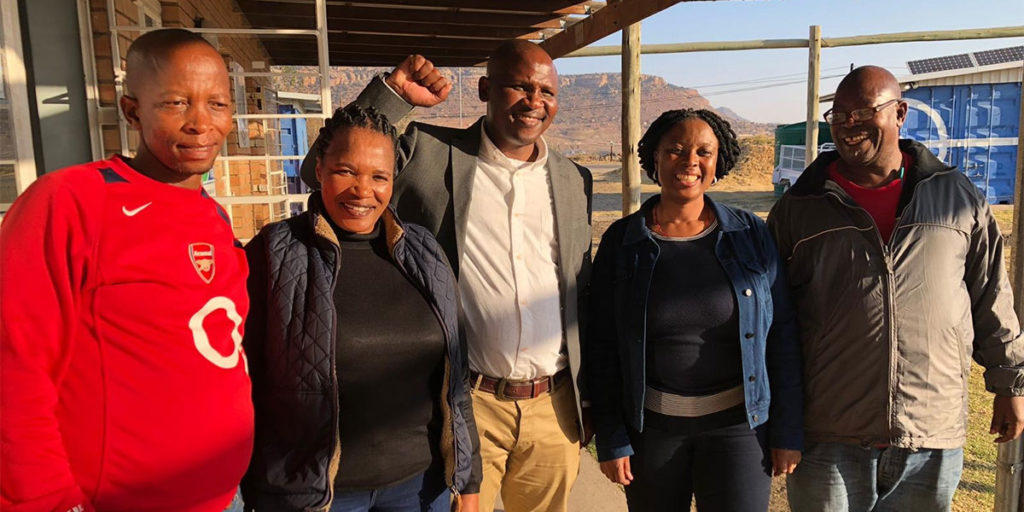

This program arises from years of worker organizing at Nien Hsing by the Independent Democratic Union of Lesotho (IDUL), United Textile Employees (UNITE), the National Clothing Textile and Allied Workers Union—and from years of women’s rights advocacy by the Federation of Women Lawyers in Lesotho and Women (FIDA) and Law in Southern African Research and Education Trust-Lesotho (WLSA). The coalition of worker and feminist organizations formed by these groups is at the heart of this breakthrough. The Solidarity Center, Workers United, and the WRC supported the Lesotho leaders’ efforts to forge these agreements and sat at the negotiating table with them, the brands, and the employer. The Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), the Fair Food Standards Council (FFSC), and the Worker-driven Social Responsibility Network (WSR-N) provided key technical and strategic advice.

These agreements arose from an investigation of Nien Hsing’s Lesotho factories by the WRC, which exposed severe and extensive sexual harassment and coercion at the supplier. Offsite interviews with dozens of Nien Hsing workers revealed that managers and supervisors coerced many workers into sexual relationships and subjected women to frequent sexual harassment. One worker told the WRC, “Many supervisors demand sexual favors and bribes from prospective employees. They promise jobs to the workers who are still on probationary contracts. […] All of the women in my department have slept with the supervisor. For the women, this is about survival and nothing else… If you say no, you won’t get the job, or your contract will not be renewed.” The WRC recommended that the unions and women’s groups join forces and pursue binding agreements with the brands, strong enough to combat this scourge of workplace sexual abuse. We urged the brands to enter negotiations toward this end which, to their credit, they agreed to do.

“Many supervisors demand sexual favors and bribes from prospective employees. They promise jobs to the workers who are still on probationary contracts. […] All of the women in my department have slept with the supervisor. For the women, this is about survival and nothing else… If you say no, you won’t get the job, or your contract will not be renewed.”

– Nien Hsing worker interviewed by the WRC

Sexual harassment and coercion are a widespread problem across countries and industrial sectors, as described by victims and numerous reports, which is in no way limited to Lesotho, or Nien Hsing, or the supply chains of the particular brands that source from Nien Hsing. Gender-based violence and harassment is especially severe in workplaces where the power imbalance is the greatest, such as the garment industry. It does not occur in a vacuum; it happens at the nexus of workers’ intersecting vulnerabilities—which can be rooted in economic destitution, societal discrimination, and/or a degraded labor rights landscape—and a setting in which workers can be abused with impunity. Workers who choose to report instances of gender-based violence or harassment typically face retaliation. One worker at Nien Hsing who was subjected to inappropriate comments and touching by her supervisor told the WRC, “There was a point I decided to go tell personnel what he was doing. I explained what he was doing, and they said they would fix it. No action was taken…” This worker was later fired based on a complaint made against her by the same supervisor.

In a context where government enforcement of laws to protect workers from gender-based violence and harassment are notoriously weak, brands and retailers rely heavily on their own voluntary codes of conduct and social auditing schemes to address labor conditions in their global supply chains. These voluntary systems—in effect, a process of corporate self-regulation—have repeatedly failed to detect and remedy abuses. In these audits, workers are interviewed onsite, in the factory, where they usually feel unable to speak candidly about labor conditions in general, much less about issues as sensitive as gender-based violence and harassment. Managers often pressure workers not to tell auditors the truth, a dynamic present at Nien Hsing, further reducing the chances that onsite interviews will yield meaningful testimony. At the same time, the voluntary nature of corporate codes of conduct means that even if instances of gender-based violence or harassment are detected, there is no obligation for the brands and retailers to require their suppliers to hold perpetrators accountable.

Enforceable brand-worker agreements represent a fundamentally different approach, in which the brands are obligated to use their economic power to compel adherence by the supplier to strong labor rights standards. These new agreements on gender-based violence and harassment create an independent office with the power to investigate worker complaints, expose managers who have harassed and abused workers, and order the company to impose punishments, including termination, whenever warranted. The complaint mechanism is modeled after the CIW’s Fair Food Program, and its monitoring body, the FFSC, which have been extraordinarily successful in eradicating sexual harassment and coercion in US agriculture. In stark contrast to internal factory complaint mechanisms, which expect workers to trust the very managers who allow and at times commit abuses, the agreements will provide workers with a safe channel, via the Lesotho women’s rights organizations, to report abuses. A comprehensive training program for workers will be led by the unions and women’s rights groups, who are guaranteed access to the factories for this purpose. If Nien Hsing does not comply with any of these commitments, each of the brands is contractually obligated to independently reduce its orders, to a degree sufficient to commercially incentivize the company to reverse course.

Enforceable brand-worker agreements represent a fundamentally different approach, in which the brands are obligated to use their economic power to compel adherence by the supplier to strong labor rights standards.

Implementation of this program will be led by the unions—IDUL, UNITE, and NACTWU—and by the women’s rights advocates at FIDA and WLSA. Crucially, the agreements protect workers and the unions from any form of anti-union retaliation or interference. The Solidarity Center, which possesses invaluable experience helping to establish and operate labor rights programs in dozens of countries across the globe, will spearhead international support for the Lesotho groups on the implementation process. Workers United, the WRC, CIW, the FFSC, and the WSR-N will all provide support and advice.

It is also important to acknowledge the willingness of the brands, and Nien Hsing, to make the unprecedented labor rights commitments encompassed in these new agreements. As previously stated, sexual harassment is not limited to this supplier or to the supply chains of this set of brands. What is unique in the garment industry is the decision of these corporations to make enforceable commitments to address the problem.

Speaking on the occasion of the announcement of these ground-breaking agreements, Thusoana Ntlama and Libakiso Matlho, of FIDA and WLSA, respectively, said, “This is the first initiative in Lesotho that brings together workers, unions, women’s organizations, and employers to work towards one common goal of improving the socio-economic rights of women in the workplace.” These agreements, in addition to offering hope of progress for more than 10,000 workers in Lesotho, set a global precedent in the fight against gender-based violence and harassment in the workplace. They represent another step forward for the model of enforceable brand-union agreements, increasingly known as worker-driven social responsibility agreements or “WSR,” which have succeeded—from the garment factories of Bangladesh to the dairy farms in Vermont—in helping workers achieve the labor rights advances that voluntary industry initiatives have consistently failed to produce.